I’ve often said to my friends and family, “it’s not that I don’t sleep enough, it’s that I seem to naturally sleep at the wrong times.” Can you relate?

I’ve often said to my friends and family, “it’s not that I don’t sleep enough, it’s that I seem to naturally sleep at the wrong times.” Can you relate?

If I was left to my own devices and had nothing to be up for in the morning, I would probably sleep between 2.00 am and 10.00 am. It often takes me at least until 12.00 to properly wake up, so my “alert time” is definitely not in the morning!

I’ve long been aware that I am a “night owl” – and for some reason, we always get looked down on by the “larks” as if their natural body clock is somehow better than ours. Anyway, that’s a story for another day, but I thought I’d share with you some of the research I’ve done into the Circadian Clock, since it is responsible for our natural sleep patterns and – importantly – can be influenced by external factors and techniques you might find helpful.

[Update: If you’re interested in learning How I Overcame Insomnia in 10 Steps, I’ve written an article series on my method.]

What is the Circadian Clock?

The Circadian Clock, or Circadian Rhythm, also known as the body clock, is a 24-hour physiological cycle present in all mammals including humans. It is controlled by a part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) of the hypothalamus. The Circadian Clock takes its cues from external factors such as daylight and temperature, and controls the secretion of certain hormones, particularly those involved in the regulation of sleep and eating.

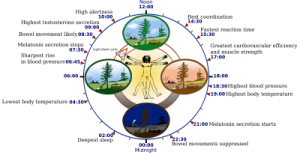

Circadian Clock Diagram from Wikipedia

Since humans are diurnal (awake during the day) our Circadian Clock is synchronised to the daylight hours and is roughly congruent with the Earth’s 24-hour rotation period (although not exactly: studies indicate that most people’s Circadian Clock falls somewhere between 23.5 and 24.5 hours, when left to naturalise under conditions where no natural daylight is seen). The word Circadian comes from Latin circa (“approximately”) and diem (“day”).

How does the Circadian Clock work?

The Circadian Clock regulates sleeping, eating, hormone production, cell regeneration and brainwave activity. Retinal cells of the eyes are sensitive to natural daylight, particularly the shorter-wave blue light characteristic of early morning light. These cells send neural signals to the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), which then signals to the pineal gland to suppress the production of melatonin, a hormone which brings about the drowsiness needed to fall asleep.

At the other end of the cycle, a drop in the amount of daylight reaching the retinal cells signals the SCN that it is night time, and the SCN in turn signals the pineal gland to begin secreting melatonin.

Other hormones controlled and regulated by the Circadian Clock include cortisol (produced by the adrenal glands, and which has an anti-stress, anti-inflammatory function), growth hormone, and thyrotropin, which is suppressed during the sleep cycle.

Melatonin production begins around 8.00 – 9.00 pm with a fall in natural light, peaks at around 2.00 – 3.00 am, and then stops at around 7.00 – 8.00 am. There is also another, smaller peak of melatonin production at around 2.00 – 3.00 pm (the “post-lunch dip”) which suggests that the Circadian Clock is also involved in the feeding cycle, and also that our bodies may benefit from an afternoon nap.

Although the SCN uses information from the eyes’ retinal cells as a cue, the Circadian Clock is not entirely dependent on light, and will continue to be regulated by the SCN even in complete darkness. People who live in very northern regions, where winter days are almost completely dark, still continue to display Circadian cycles.

However, without regular exposure to natural light, after a while the Circadian Clock can fall out of synchronisation to the Earth’s cycle of darkness and light over 24 hours.

Artificial light is not usually sufficient to synchronise the Circadian Clock, which explains why shift workers find it difficult to adjust to a pattern of sleeping during the day and being awake in the night. Their Circadian Clock is working against them and continuing to produce melatonin at night time.

However, it only takes a few days to adjust to a new light and dark pattern when moving to another part of the Earth, as demonstrated by the experience of jet-lag. For a day or two, the Circadian Clock tries to continue producing melatonin at the original sleeping time, however the cues from the daylight cycles in the new region fairly quickly enable the Circadian Clock to re-synchronise.

When disrupted, the sleeping and eating patterns can fall out of balance and correlates with physical problems such as cardiovascular health and obesity, and mental problems including bipolar and depression.

Circadian Clock Chronotypes

Human Circadian Clocks can vary from person to person up to around 2 hours difference, which explains the phenomenon of “larks” and “night owls”, where some people naturally seem to sleep and wake earlier, while others’ patterns start and end later in the day.

The different patterns followed by Circadian Clocks are sometimes called different “chronotypes”. Cycles can also change over a person’s lifetime – babies take a few months to establish their Circadian Clocks, children and teenagers need more sleeping time while older adults find they sleep less.

Circadian Clock disorders

Shift-workers and people suffering from jet-lag are two examples of Circadian Clock disorders which can cause physiological and psychological problems. However these are caused by external factors and can be remedied by re-synchronising the Circadian Clock.

However, some people suffer from an internal imbalance in their Circadian Clock which goes beyond the natural chronotype range, which can cause serious social and physiological problems. This is known as Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder (CRSD). There are some treatment options available including dark therapy (the use of goggles which block out the short-wavelength blue light at certain times of day) and melatonin supplementation, but the cycle is intrinsically out of balance and often cannot be “fixed” permanently.

However the majority of people who have a disrupted Circadian Clock can find relief by re-synchronising their cycle to the Earth’s cycle of darkness and light.

How to re-synchronise your Circadian Clock

If your Circadian Clock has become disrupted or fallen out of balance, it is possible to help guide it back into synchronisation with the daylight patterns.

- Schedule. Stick to a consistent schedule of sleeping and eating, even on weekends. The Circadian Clock also takes its cues from mealtimes so try to keep these to a schedule too.

- Morning Light. Increase your exposure to natural light first thing in the morning, by getting outside before breakfast, or standing by a bright window on waking.

- Evening Darkness. Avoid exposure to bright lights in the evening, especially short-wavelength blue light, which is characteristic of the light emitted by devices such as tablets, laptops and mobile phones. Limit the use of devices with screens in the evening or install a blue-light filter.

So, I hope that information was helpful to someone out there. For quite a while now I have used a blue-light filter on my mobile phone when I use it after about 8.00pm. The one I use is Eye Protect Blue Light Filter from the PlayStore (I don’t know if it is available for iphone, but there are many other versions that do the same thing). The reason I like this one is because it is free, it doesn’t require any special permissions or display ads, it’s just a simple filter that you can easily turn on and off when you want it.

If, like me, you’re a Night Owl who struggles to wake up early, you could try putting some of these techniques to work in your daily routine. Using a blue-light filter certainly seems to help a bit, another way to address the light issue is to put on a podcast and listen to information instead of reading it.

As for morning light, I’ve tried experimenting with leaving the curtains open for morning sunshine to wake me up (it works, by the way! But the street lamp outside my window also keeps me up at night, so I’m still working on getting around that).

The best thing I’ve found for helping wake me up especially in winter when the mornings are dark, is the Lumie Bodyclock Starter 30 alarm clock, which has a lamp that gradually increases in brightness before the time you want to wake up, simulating a natural sunrise. I’ve had mine for over a year and I really love it. You can read my review of the Lumie alarm clock here.

[UPDATE: The Lumie Starter 30 has been replaced by the Lumie Bodyclock Spark 100, which has similar features and is around the same price on Amazon, £60ish. I will be writing a review of this product soon.]

That’s it from me today. Hope some of this information and techniques were useful.

[…] written before about the Circadian Clock and how you can support it by doing certain things at certain times of the day and night to help […]

[…] The Circadian Clock is a daily hormonal cycle regulated by part of the hypothalamus in the brain. It is usually synchronised to the Earth’s natural cycle of darkness and light (rotational period) hence the Latin circa (‘about’) + diem (‘day’). It takes its cues from natural sunlight to keep it in check, but can fall out of kilter, especially in artificial light, and stressful events and environments. The Circadian Clock regulates the production of melatonin (hormone promoting sleep) in the evenings, and cortisol (alertness hormone produced during exercise and stressful situations) in the mornings. For more information, read this article on the Circadian Clock. […]

[…] naps don’t necessarily need to be completely avoided, and in fact our natural Circadian Clock includes a small peak in melatonin between 2pm and 3pm (the post-lunch dip) where a short nap would […]